History and heritage

June 16 1976: The day youth changed South Africa's history

- This Youth Day, follow real-time tweets of the events of 16 June 1976 on @SA_info via the #SowetoUprising hashtag.

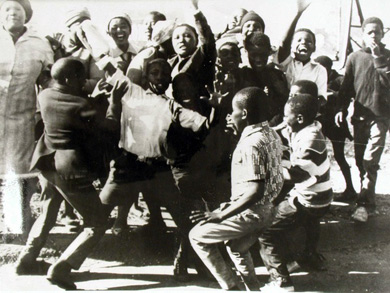

Protesting Soweto students in 1976. (Image: Doing Violence to Memory)

Protesting Soweto students in 1976. (Image: Doing Violence to Memory)

Background: An education denied

By 1976, the frustration had been building for a generation. Young black South Africans knew their schooling was the worst in South Africa. In 1953, the new National Party government had passed the Bantu Education Act, which made sure black youth were educated only to the point that they could be servants to white people's prosperity. Before then, South Africa had a rich tradition of mission schools. Nelson Mandela, Robert Sobukwe, and many others had been given the opportunity to become some of the best minds in South Africa as a result of their quality schooling. But the apartheid government wanted the threat of bright African minds to stop. Many mission schools were closed. By 1976, students' frustration reached boiling point when the government began to introduce Afrikaans as the language of teaching. Black students, particularly in the cities, were fluent only in African languages and in English. Few knew Afrikaans well enough to be taught in it, let alone write exams in the language.

The mood at the start of the march - before the police opened fire - was hopeful and excited. (Image: South African History Online)

The mood at the start of the march - before the police opened fire - was hopeful and excited. (Image: South African History Online)

07:00

It is a Wednesday morning, 16 June 1976. Today, the Soweto Students Action Committee have organised the township's high school pupils to march to Orlando Stadium, as a protest against the government's new language policy. The student leaders come mainly from three Soweto schools: Naledi High in Naledi, Morris Isaacson High in Mofolo, and Phefeni Junior Secondary, close to Vilakazi Street in Orlando. The protest is well organised. It is to be conducted peacefully. The plan is for students to march from their schools, picking up others along the way, until they meet at Uncle Tom's Municipal Hall. From there they are to continue to Orlando Stadium.

The children of Soweto were in high spirits at the promise of the protest. (Image: Doing Violence to Memory)

The children of Soweto were in high spirits at the promise of the protest. (Image: Doing Violence to Memory)07:30

Students gather at Naledi High. The mood is high-spirited and cheerful. At assembly the principal gives the students his support and wishes them good luck. Before they start the march, Action Committee chairperson Tepello Motopanyane addresses the students, emphasising that the march must be disciplined and peaceful. At the same time, students gather at Morris Isaacson High. Action Committee member Tsietsi Mashinini speaks, also emphasising peace and order. The students set out. On the way they pass other schools and numbers swell as more students join the march. Some Soweto students are not even aware that the march is happening. "The first time we heard of it was during our short break," said Sam Khosa of Ibhongo Secondary School. "Our leaders informed the principal that students from Morris Isaacson were marching. We then joined one of the groups and marched." There are eventually 11 columns of students marching to Orlando Stadium - up to 10 000 of them, according to some estimates.

09:00

There have been a few minor skirmishes with police along the way. But now the police barricade the students' path, stopping the march. Tietsi Mashinini climbs on a tractor so everyone can see him, and addresses the crowd. "Brothers and sisters, I appeal to you - keep calm and cool. We have just received a report that the police are coming. Don't taunt them, don't do anything to them. Be cool and calm. We are not fighting." It is a tense moment for police and students. Police retreat to wait for reinforcements. The students continue their march.

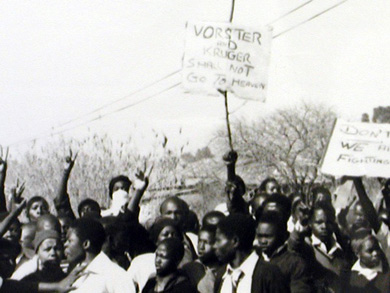

By Thursday 17 June 1976 the student uprising had spread to Alexandra township in the far north of Johannesburg.

By Thursday 17 June 1976 the student uprising had spread to Alexandra township in the far north of Johannesburg. The placard in the centre reads: "Vorster and Kruger shall not go to heaven."

In 1976, JB Vorster was prime minister of the apartheid government, and Jimmy Kruger his minister of police.

The placard on the right - partly cut off - reads simply: "Don't shoot. We are not fighting."

(Image: Doing Violence to Memory)

09:30

The marchers arrive at today's Hector Pieterson Square. Police again stop them. It was here that everything changed. There have been different accounts of what actually started the shooting. The atmosphere is tense. But the students remain calm and well-ordered. Suddenly a white policeman lobs a teargas canister into the front of the crowd. People run out of the smoke dazed and coughing. The crowd retreats slightly, but remain facing the police, waving placards and singing. Police have now surrounded the column of students, blocking the march at the front and behind. At the back of the crowd a policeman sets his dog on the students. The students retaliate, throwing stones at the dog. A policeman at the back of the crowd draws his revolver. Black journalists hear someone shout, "Look at him. He's going to shoot at the kids." A single shot rings out. Hastings Ndlovu, 14 years old, is the first to be shot. He dies later in hospital. After the first shot, police at the front of the crowd panic and open fire.

The Hector Pieterson Memorial in Soweto. (Image: Brand South Africa)

Twelve-year-old Hector Pieterson collapses, fatally injured. He is picked up and carried by Mbuyisa Makhubo, a fellow student, who runs towards Phefeni Clinic. Pieterson's crying sister Antoinette runs alongside. The moment is immortalised by photographer Sam Nzima, and the image becomes an emblem of the uprising.

There is pandemonium in the crowd. Children scream. More shots are fired. At least four students have fallen to the ground. The rest run screaming in all directions.

The Hector Pieterson Memorial in Soweto. (Image: Brand South Africa)

Twelve-year-old Hector Pieterson collapses, fatally injured. He is picked up and carried by Mbuyisa Makhubo, a fellow student, who runs towards Phefeni Clinic. Pieterson's crying sister Antoinette runs alongside. The moment is immortalised by photographer Sam Nzima, and the image becomes an emblem of the uprising.

There is pandemonium in the crowd. Children scream. More shots are fired. At least four students have fallen to the ground. The rest run screaming in all directions.

10:00

Dr Malcolm Klein, a coloured doctor in the trauma unit at Baragwanath Hospital, is on his break when a nurse summons him with a look of utter distress on her face.

Bloodied, injured and dying students were ferried to Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto. (Image: Doing Violence to Memory)

Bloodied, injured and dying students were ferried to Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto. (Image: Doing Violence to Memory)"I followed her and was met by a grisly scene: a rush of orderlies wheeling stretchers bearing the bodies of bloodied children into the resuscitation room," he recalled later. "All had the red 'Urgent Direct' stickers stuck to their foreheads ... "I stared in horror at the stretcher bearing the body of a young boy in a neat school uniform, a bullet wound to one side of his head, blood spilling out of a large exit wound on the other side, the gurgle of death in his throat. Only later would I learn his name: Hastings Ndlovu."

12:00

After the first massacre, the students flee in different directions. Anger at the senseless killings inspires retaliation. Buildings and vehicles belonging to the government's West Rand Administrative Buildings are set alight and burned to the ground. Bottlestores are burned and looted. More students are killed by police, particularly in encounters near Regina Mundi Church in Orlando and the Esso garage in Chiawelo. As students are stopped by the police in one area, they move their protest action elsewhere. By the end of the day most of Soweto has felt the impact of the protest. Schools close early, at about noon. Many students, so far unaware of the day's events, walk out of school to a township on fire. Many join the protests. The uprising gains intensity.

21:00

Fires continue blazing into the night. Armoured police cars later known as "hippos" start moving into Soweto. Official figures put the death toll for that single day at 23 people killed. Other reports say it was at least 200. Most of the victims are under 23, and shot in the back. Many others are maimed and disabled.

Aftermath

The uprising spreads across South Africa. By the end of the year about 575 people had died across the country, 451 at the hands of police. The injured number 3 907, with the police responsible for

2 389 of them. During the course of 1976, about 5 980 people are arrested in the townships. International solidarity movements are roused as an immediate consequence of the revolt. They soon give their support to the pupils, putting pressure on the apartheid government to temper its repressive rule. Many schoolchildren leave South Africa, to join the exiled liberation movements. This pressure is maintained throughout the 1980s, until resistance movements are finally unbanned in 1990.

Sources and additional information

This is largely an edited and condensed version of the timeline published by South African History Online in the feature The June 16 Soweto Youth Uprising. Journalist Lucille Davie has written many excellent accounts of the events of June 16 1976. These include:

- 16 June 1976: 'This is our day'

- The day Hector Pieterson died

- Hastings Ndlovu: Forgotten hero of 1976

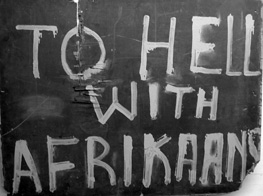

A placard from the student protest. The events of 16 June 1976 were sparked by the apartheid government imposing Afrikaans as the language of teaching in black schools.

A placard from the student protest. The events of 16 June 1976 were sparked by the apartheid government imposing Afrikaans as the language of teaching in black schools.

Related links

Related articles

- 40 South Africans Under 40 Part 1

- Grab your chance: June 16 Youth Expo in Johannesburg

- Constitution Hill's Basha Uhuru Arts Festival on now

- 16 June 1976: 'This is our day'

- On the trail of the 16 June '76 students

- Hastings: forgotten hero of 1976

- The day Hector Pieterson died

- Regina Mundi - Queen of Soweto