Remembering Nelson Mandela's first steps of freedom

11 February 2015

Nelson Mandela walked through the gates of Victor Verster Prison because he insisted on

doing so.

If he didn't have his way he would have been dropped off at his small house in Soweto,

1 400 kilometres away.

Just two days before, President FW de Klerk told him he would be flown to Johannesburg

and released in Soweto. Mandela refused.

He also asked for another week in prison to allow his comrades outside to prepare

properly. De Klerk refused.

So on Sunday, 11 February 1990, millions of people around the world watched as

Mandela took his first steps of freedom in 10 050 days through the gates of the

last prison he was detained in.

It was nine days after De Klerk legalised the African National Congress and the Pan

Africanist Congress and announced that Mandela would soon be freed.

It was 27 years, six months and four days since South Africa's most wanted man had

been arrested at a roadblock

outside the eastern town of Howick. The father of five

young children from two marriages walked to freedom as a 71-year-old grandfather.

Newspapers

One would have expected some jubilation from the man who had endured two criminal

trials, two prison sentences and time in four prisons. But all who encountered Mandela

in the days leading up to his release were struck by his calmness.

Trevor Manuel visited him in prison soon after De Klerk had announced that he would

leave the prison the next day. When he arrived at the house where Mandela had been

held for the last 14 months of his imprisonment, he found him already in his pyjamas.

On the day of his release Mandela was up early as usual, read the newspapers over

breakfast and even had his daily nap as thousands of supporters and journalists

gathered outside the prison.

Children had been born since his capture and had grown into adults; many became

freedom fighters themselves,

inspired by the sacrifice of Mandela and his comrades.

They had been detained, tortured, forced into exile and killed. Some encountered him as

fellow political prisoners.

Dignity

While some young firebrands grew frustrated with his manner, he impressed them in jail

with his dignity. He made a conscious decision to hold on to it at all costs.

"I believe the way in which you will be treated by the prison authorities depends on your

demeanour and you must fight that battle and win it on the very first day," he said to

journalists some years after his release.

While some prison authorities were brutes, there were some with whom he formed

friendships. One was Jack Swart, who was Mandela's last warder. Even Swart, who

spent every day of 14 months with him, did not notice him as anything but calm as he

prepared for freedom.

In the searing summer heat of 11 February 1990 Mandela and his wife Winnie walked a

few metres towards the

crowd lining the road outside the prison. Freshly-sewn flags in

the colours of the African National Congress were held aloft. Just ten days earlier,

merely having one could have earned them a vicious beating from police and even time

in prison.

Negotiations

For the last three years of his imprisonment Mandela was involved in secret discussions

with the apartheid regime with a view to setting up eventual multiparty negotiations to

end apartheid.

Ironically this is what he was calling for before he was jailed. His letters in1961 to Prime

Minister HF Verwoerd were ignored, so he called for a strike against South Africa

becoming a republic, away from the Commonwealth Group of Nations.

A peaceful solution out of the question, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, a partner in South

Africa's first black law firm became the first Commander-in-Chief of Umkhonto we

Sizwe, the military wing of the ANC.

Passive resistance

Mandela

and Gandhi were often named in the same sentence when extolling the virtues

of passive resistance.

Mandela put the matter to rest after his release when he said:

"If the conditions demanded, as they were, that we should avoid any form of

action which would lead to bloodshed, I would avoid that. But if the conditions were

such that one could depart from a non-violent struggle I would do so. That's why we

resorted to violence, for example. Because the conditions demanded that we should take

up arms. The government had banned our organisation, it had sent people to exile,

thrown others to jail, gagged those who were inside and imposed ruthless repression. In

that situation it was proper to take up arms. Gandhi would never have agreed."

Mandela went on a seven-month tour through Africa and to London in 1962 to raise

support for the armed struggle and to undergo military training. He was captured soon

after his return to South

Africa. He was tried and sentenced on 7 November 1962 to five

years in prison. His crime? Leaving the country without a passport and inciting a strike.

Sabotage

Ten months into his sentence he was brought to court on charges of sabotage relating to

the ANC's attacks on strategic installations in which no-one but a fellow freedom fighter

was killed. Facing the death penalty, Mandela and Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Ahmed

Kathrada, Raymond Mhlaba, Denis Goldberg, Elias Motsoaledi and Andrew Mlangeni

were sentenced to life imprisonment on 12 June 1964.

During his imprisonment Mandela fought to improve prison conditions; demanded in

vain for anti-apartheid fighters to be recognised as political prisoners; brought his legal

skills to the aid of fellow inmates and urged unity between political organisations.

Slowly, as the campaigns grew outside the prison walls, so did Nelson Mandela's stature

in the imagination of those opposed to

apartheid.

Expectations

"Rolihlahla Mandela, freedom is in your hands; show us the way to freedom in this land

of Africa," are some of the words of just one of many songs highlighting him as a

saviour. Each refrain placed firmly on his shoulders, the expectations of millions.

He rejected several offers of conditional release, the last made on 31 January 1985. This

time President PW Botha insisted that abandoning violence would be the only way to

secure one's freedom.

In his reply to Botha, Mandela wrote: "The coming confrontation will only be averted if

the following steps are taken without

delay.

- The government must renounce violence first

- It must dismantle apartheid

- It must unban the ANC

- It must free all who have been imprisoned, banished or exited for their opposition to

apartheid

- It must guarantee free political activity."

As the struggle within and outside

South Africa intensified, successive states of

emergency were imposed, giving security forces a free hand in detaining opponents of

the state indefinitely.

By the end of 1985, when many parts of South Africa were literally in flames, Nelson

Mandela was taken from his Pollsmoor prison cell to hospital. He needed prostate

surgery and surgeons of his own choice were seconded onto the medical team.

Conversation

While en route from Johannesburg to visit him, his wife encountered Justice Minister

Kobie Coetsee on the flight. She engaged him in conversation and encouraged him to

visit her husband in hospital.

The hospital meeting on 17 November 1985 was the moment Nelson Mandela needed.

On his discharge he reached out to Coetsee and the first in a series of meetings took

place the following year.

In August 1988, Mandela was admitted to another hospital where he was diagnosed with

tuberculosis. He was treated at two different

hospitals until 7 December when he was

transferred to Victor Verster Prison.

By then Goldberg and Mbeki had already been released and Mandela used his contacts

with the government to call for the release of the remaining Rivonia trialists.

On 15 October 1989 Sisulu, Kathrada, Mhlaba, Motsoaledi and Mlangeni were freed with

Oscar Mpetha, Wilton Mkwayi and Jeff Masemola.

Unbanned

South Africa was still under a state of emergency when the regime released Mandela,

but it had unbanned the organisations, allowed exiles to return and begun to free

political prisoners.

Mandela had not been expected to renounce violence.

Within months of his release, the ANC delegation, which included returned exiles, sat

down with the government team. These bilateral talks led to multi-party negotiations

beginning in December 1991 and ending in November 1993 with the setting of an

election date for 27 April 1994.

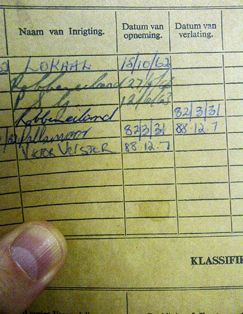

As President of South

Africa, Nelson Mandela – prisoner number 19476/62, 11657/63,

466/64, 220/82 and 1335/88 – laid the first bricks in the building of a new foundation to

hold his motherland for future generations. Nelson Mandela and his comrades pulled

South Africa back from the precipice, but the country faced a long and arduous battle

ahead.

Source: Nelson

Mandela Foundation

Nelson Mandela on the balcony of the Cape Town City Hall on the day of his release. (Image: Miguel Ribeiro, Nelson Mandela Foundation)

Nelson Mandela on the balcony of the Cape Town City Hall on the day of his release. (Image: Miguel Ribeiro, Nelson Mandela Foundation)

Nelson Mandela's prison card shows the date of his first incarceration on Robben Island as 27/05/1963 (Photo: Nelson Mandela Foundation)

Nelson Mandela's prison card shows the date of his first incarceration on Robben Island as 27/05/1963 (Photo: Nelson Mandela Foundation)

On display at the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg: the famous photo of Nelson Mandela congratulating Springbok captain Francois Pienaar after South Africa beat New Zealand to clinch the 1995 Rugby World Cup. Both men are wearing the number six captain's jersey.

On display at the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg: the famous photo of Nelson Mandela congratulating Springbok captain Francois Pienaar after South Africa beat New Zealand to clinch the 1995 Rugby World Cup. Both men are wearing the number six captain's jersey.

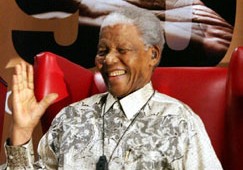

Nelson Mandela greets the audience at his 90th birthday celebration launch in Johannesburg (Photo: Lucky Nxumalo / Nelson Mandela Foundation)

Nelson Mandela greets the audience at his 90th birthday celebration launch in Johannesburg (Photo: Lucky Nxumalo / Nelson Mandela Foundation)